I have alluded to using this blog to pull-through sales of my works of fiction, and it just occurred to me that perhaps giving my blog readers a sample of my writing might better encourage sales of the books. So, here is a previously unpublished example that I hope you enjoy. It is NOT a work of fiction however. Many years ago, my younger brother and I had the chance to visit the ruins of Nan Madol on the Pacific island of Ponape just a year after the long-standing tabu against visits to the ruins was lifted by the islanders. I documented this Indiana Jones-type adventure, but never got around to publishing it; so here it is, complete with a few photos that I took at the time.

The Mystery City of Nan Madol

I first became aware of Nan Madol in 1980, while scanning through one of those silly paperbacks about ancient astronauts. A fuzzy picture had been inserted on a page that detailed the author’s assertion that it was a space base for the saucer people. I paused to take a look. The photo was obviously taken by an amateur, as it was off-center and largely composed of a boring expanse of ocean. In the lower right of the image was a shock of green vegetation; a Mangrove swamp that marched into the sea. As I focused closer on the grainy image, the patch resolved into individual trees growing around dark slabs of rock that constituted a gigantic wall draped with a riot of tangled vines and leaf pads. In the hard to distinguish background was an out of focus view of some decomposed rock structures that were once buildings of some kind. The caption beneath the photo stated, “Nan Madol on the island of Ponape, the Atlantis of the Pacific”.

I grabbed my dog-eared atlas and found it: A tiny isolated dot near the equator in the Western Pacific. Positioned thousands of miles from either Asia or the New World, it was an extremely weird location for megalithic ruins. Setting aside the problem of its isolation, I considered the stupor inducing tropical heat at the equator, and the laid back lifestyle of most Pacific islanders. There could have been no writing, or ego-mad pharaohs with disciplined troops cracking the whip over slaves who strained to the ropes.

I scanned the text in the atlas: 164 square miles; mountainous, with peaks that rise abruptly to over a thousand feet above the level of the sea. Embraced and protected by the beautiful Nankapenparam reef. The largest of the Caroline Islands, and capitol of a newly formed and loose confederation of Micronesian peoples. Contains gigantic prehistoric ruins on the southeast coast called Nan Madol. I determined to delve into the mystery further. After researching a bit at the University of Utah library, I found that the first Europeans to visit Ponape arrived in 1595, and consisted of the crew of the San Jeronimo under Pedro Fernandez de Quiros. After a friendly exchange between the crew and the natives, the ship continued on its way to Manila.

Years later, James O’Connell, the survivor of an 1826 shipwreck, washed ashore and was the first representative of western civilization to see Nan Madol.The ruins sprawl over eleven square miles and are of uncertain date and origin. Erected astride some low-lying islands in a shallow coastal bay, they are huge, awesome and somewhat menacing. It is a city of stone frozen in time. The literature regarding Nan Madol was sparse at the time and filled with more fantasy than fact. The cultists point to Nan Madol as certain proof of a high-order civilization on a ‘Lost’ Pacific continent that was now submerged in the depths. Modern Archaeologists believe that it dates from the 1400s at a period when the population was unified under one ruler. When Ponape was discovered by de Quiros, the island was divided into five warring kingdoms, and the ruins were deserted.

The natives have an oral history of conflicting myths about it, which involve magic, men who could fly, and teleportation of the tremendous stone building blocks.The tradition divides Nan Madol into several districts; The main center, ‘Madol-Pa’, where the king lived, and ‘Madol-Pau-Ue’, which contained Nan Towas, the largest structure in the city and said to be the burial place for the Satalurs–the kings of Ponape. Adjacent to Nan Towas was the house of Priests, and beyond, the governmental center and alters. Until the late 1970s, the area of the ruins was considered tabu by the islanders, although they apparently used it infrequently until the late 1800s as a center for the worship of the turtle god Nanusunsap.

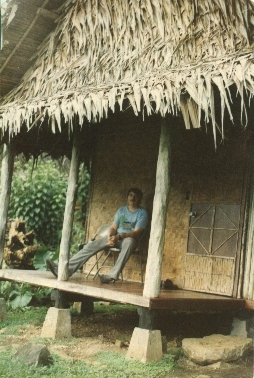

In the spring of 1982 I had occasion to travel to the South Pacific with my younger brother on a research project, and determined to experience the gestalt of Nan Madol myself, I persuaded my brother to agree to an accommodating change in our itinerary. We thus arrived on wings of steel in early April. The island was cloaked in a luxurious tropical rainforest that changes into Mangrove swamps on the margins of the sea, and as our beaten up 737 touched down, I looked through the curving window at rugged mountains shrouded by pregnant clouds. A short, bounding ride from the airfield up a steep and muddy road brought us to our mountain base camp, the Hotel Ponape.

After having spent the previous several weeks in the more primitive islands of the South Pacific, we were delighted by the synthesis of tropical simplicity and modern technology provided by the hotel; the ‘rooms’ were simple thatched huts that were electrified, screened to keep out the insects, and equipped with all of the conveniences, including a shower in an enclosed tiny courtyard filled with tropical plants and flowers. That evening, we enjoyed the novelty of hot running water, and much later, after luxuriating in the shower, sat on the veranda outside. Swooping through the air, with four-foot wingspans, the giant fruit-eating bats called ‘Flying Foxes’ sailed between the Coconut and Pandanas trees in the moonlight. Below us, the placid water of the bay reflected the twinkling isolated lights of a distant village on the jungle’s edge.

The following morning, we tried to cajole some of the native Micronesians to take us around the island to Nan Madol, but it was nothing doing. To most, it was still tabu. Luckily, we found a family of Polynesians who were not fearful, and we hired one of them to take us in his power boat to the reef on that side of the island for some apparent spearfishing. As several boats of Micronesian fishermen were nearby, we just floated with the snorkels, looking at the rainbows of coral and fish that intermingled in patterns like kinetic art at the museum; one moment blending, the next standing out in sharp contrast. In the afternoon, when the fishermen left with their haul, we took a kidney-jolting ride across the lagoon to Nan Madol. We approached the ruin along a series of interconnecting islands which formed the rim of a huge bay. As we got closer, the natural features of the waterways between the jungle-covered islets transformed into channels cut with geometric precision and ranked with dense vegetation. Further on, we could see canals lined with immense blocks of stone. I recalled that Carbon 14 dating has shown that the Micronesian Islands had been occupied since about 1500 BC.

Our guide killed the motor and began to use a pole to push the boat through the shallows toward the ruin. In the ensuing silence, I asked about local legends of Nan Madol. As the first ones on the scene, the natives should know if it already existed when they arrived from distant shores. He related that many islanders believed the ruins were built and abandoned long before the first wave of immigrants arrived. Others believed that two ancient magicians had cast a spell and caused the stones to fly through the air and land in a sequence that resulted in the walled city of Nan Madol. It then became a great cult center to the gods, demons and ghosts.

Another tradition, more historical, relates that long ago, Ponape was conquered by the King of Kusae, an island several hundred miles to the east. A single king later arose among the islanders who eventually overthrew the conquerors and assumed the title of Satular. He then ordered the construction of Nan Madol, and awaited retaliation. It all sounded to me like feeble attempts to explain the incomprehensible.

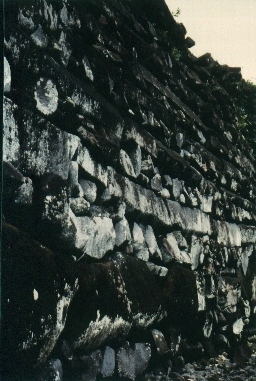

We proceeded down the major canal that led us to the interior of the citadel, a mass of crumbling stone buildings and a maze of walls. Our guide docked the boat at the base of the largest megalithic structure, which appeared on first inspection, to be a walled fortress or temple. It was Nan Towas, ‘The Place of the High Walls’, where the Satalurs were supposed to be buried. It is constructed of hundreds of elongated stones of basalt, some of which appeared to weigh twenty or thirty tons, and all seeming carved in the shape of wooden pencils. The stone, in fact, is Prismatic Basalt and was formed as gigantic six-sided crystals in a volcano off of the northern coast of Ponape. On average, the crystals used in the construction are six to ten feet long, and two to four feet in cross section. Some stones are as large as any utilized by the Incas or Egyptians, and all had been transported to the site over miles of open ocean.

I looked up at the outer wall of Nan Towas, which soared thirty feet above my head, and tried to imagine how the builders could have stacked these gargantuan stones so high. The wall enclosed a rectangle one hundred yards on a side, and was ten feet thick. As I walked through the portal to the interior, I noticed that the walls had been subtly engineered so that they curved out toward the top. Climbing one from outside of the citadel would be very difficult. The stonework was crude, the crystals having been stacked like logs, and each layer of the basalt pencils was rotated by ninety degrees with respect to the preceding layer for greater stability. This ‘cordwood’ building technique, and the varying size of the basalt pencils combined to create voids and cavities of substantial size, which had been filled with smaller rocks and broken coral. I gazed down the plane of the wall toward its distant corner. Slowly, the discontinuity of crystal ends and coral blended to form a smooth and continuous surface in my mind’s eye; and in that moment, the geometric perfection of the wall stood forth. As the curve of the walls became extremely pronounced toward the top, the corners where the walls met joined in graceful arcs reminiscent of the Pagoda style of the Orient.

Inside the enclosure, I noticed a high stone rampart about four feet wide that had been constructed against the inner surface of the walls and circuited the entire rectangle. It would have given the defenders of the citadel the position and elevation advantage necessary to repel invaders from the sea. I surmise they came from the sea, because the only points of ingress to the fortification were the portal I had just passed through and two rock-lined tunnels so small that men would have had to come through one at a time on their hands and knees. All three were on the side of the fortress facing the island and away from the sea. I scrutinized the wall in vain for signs that individual stones had been shaped or sized to fit. There were no tool marks weathered by the centuries, no Petroglyphs or sculptured patterns, just massive functionality, crudely fashioned with unique natural materials and lots of brute force.

I carefully walked across the broken stone slabs that lined the floor of the ‘courtyard’. Banyan trees jutted at random out of the patiently fitted puzzle of flooring, erupting through eons of impervious weight and purpose. Propelled sunward, they covered large areas of the intervening surface below with an umbrella of shadow. At my feet, iridescent lizards scuttled fretfully from rock to rock, pausing now and then to do a series of rapid pushups; a saurian invention to mitigate the fierce tropical heat, and perhaps raise their spirits in this somber and brooding place.

Through the checkerboard of sun and shadow, I saw that the ‘courtyard’ contained carefully spaced pits that were lined with rock, and some of them were roofed over with immense flat slabs of stone. In construction, they were similar to the Kivas found in Indian pueblos of the American Southwest, although they were rectangular, rather than round. Millennia ago, the subterranean rooms now open to the sky were foundations or basements for more elaborate and perishable structures made of wood and thatch. The covered pits would have served nicely as food storage bunkers, protecting their contents from the relentless tropical sun. Similar speculations slithered across my brain like the lizards on the rocks as I glimpsed other complex structures obscured by shadow and camouflaged in clutching vines.

Dominating the center of the citadel was an elevated stone building roofed with even more massive stone slabs that abutted one another almost seamlessly. It was about twenty by thirty feet in area and had walls constructed with the same outward curve as the citadel’s enclosure, complete with the Pagoda-like corners. There were no windows to allow the entry of light. I peered into the dim recess through the only entrance, and saw that the floor had been excavated to a depth of five or six feet relative to the surface on which I stood. The resulting subsurface floor and walls seemed smoothly continuous and were unadorned. There was no frivolity in the structure, no unnecessary embellishments, no art. The feeling of this place was not of a temple or the final resting place of kings with fancy titles. It was more like a fortress or sanctuary; severely utilitarian, stripped for action and awaiting warriors or monks. Overall, the architecture seemed delicately Oriental, yet savage, like the panel art from an adult action comic book.

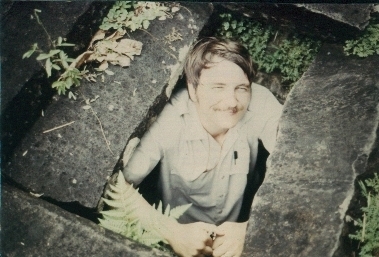

My brother, who had wandered behind the building to look around called out in excitement for me to join him. There, he had discovered a rock-lined opening in the plaza floor that was the width of a man’s shoulders and gave access to what appeared to be a lateral tunnel of unknown length and dimensions. His miniature camper’s flashlight threw its feeble foot-candle or two into the steaming blackness below. His compulsive curiosity as a scientist took over, and he leapt down into the opening to get a better look. I jumped down beside him and he batted away the lacey nets of cobweb and moved cautiously into the depths of the tunnel.

I cautiously followed behind him, fearing the worst; a cave-in, multiple bites from exotic tropical snakes, or nameless insect horrors. My fantasies dissolved as we came to the end of the tunnel only fifteen or twenty meters beyond the entrance. I shined my light around, and was amazed to see that the walls and ceiling were covered with limestone deposits, and stalactites at least six inches long festooned the roof above me. They testified to the tunnel’s great age, and made a mockery of the Archaeologist’s assertions that the place was constructed sometime after the birth of Christ. At the tunnel’s abrupt end, a large stone cross-member had been carved with Petroglyphs arrayed in rows, and reminiscent of the symbols in old Punic writings.

We took some photos of the script, then retreated back to the entrance and left the place to its Arachnid sentinels. Emerging into the damp tropical afternoon, we left the plaza to tiptoe across the uncertain rocky surface of a narrow walkway that connected the central elevated area of the plaza to the rampart of the enclosure’s great walls. Arriving at the safely of the rampart, I paused to turn and gaze toward the sea. Below me, in the foreground, was a great encircling moat. It had been laboriously excavated and lined with thousands of tree-sized volcanic pencils of basalt, but was now largely filled with silt and rubbery green leaf pads.The careful geometry of the rocky embankments was broken here and there by jagged gaps where the basaltic prisms had avalanched to the bottom in a haphazard heap over time, like pickup sticks that were partially submerged beneath the murky surface. Nearby, I could see distorted building foundations and offset canal walls that testified to a great earthquake that must have occurred centuries ago. Beyond, the surreal landscape of crumbled buildings, collapsed canals, and the encroaching rainforest terminated abruptly at the edge of the placid bay.

At the far limits of the bay where the breakers were crashing, I could see a mighty sea wall of interlocking basalt pencils that stretched into the distance. The work of thousands and the sweat of years, it had for centuries withstood the surging power of the Pacific Ocean. It was then that I realized the true enormity of Nan Madol. The vast fortress in which I stood only occupied a few thousand square yards, and was only a minor component of the eleven-square mile complex of canals and buildings.

The indigenous inhabitants of Ponape total around ten thousand at present. Perhaps, in earlier times the population may have been somewhat larger, and was reduced by the ‘Captain Cook’ syndrome, but I think it arrived at today’s stable number over the intervening years, based on resource availability and land use. I tried to imagine some fanatical dictator ordering the entire populace to man the outriggers and transport the mind-boggling basaltic prisms in their thousands across miles of sea to build Nan Madol.

Consider the organizational problems of such an enterprise. The management skills and rigid social infrastructure required to smoothly coordinate the enormous undertaking was in a class with the Aztec Pyramid of the Sun, or the pre-Inca ruin of Teohuanaco. A scenario: Assume the local inhabitants had the necessary skills and social organization. Now, of an obedient population of ten thousand, subtract one thousand of those too old or young to work. Subtract five hundred more that were crippled, sick, pregnant, or injured. From the balance remaining, distribute support assignments as follows: One thousand to engage in subsistence farming, cooking, harvesting, etc. One thousand to quarry stone. One thousand to build and row the transport canoes or rafts. Five hundred to supervise the construction.

This would leave three thousand, five hundred people available to excavate and line with rock the miles of canals and build the distant and enormous sea wall. And then, without respite, construct the Citadel and numerous adjacent buildings. It was a single-minded and heroic effort that would have taken many decades, and perhaps centuries. What terrible fear or love inspired this frenzy of monumental construction and fortification? Its battlements seemed to face the sea, vigilant toward an enemy that struck from beyond the reef and distant blue horizon.

I walked slowly around the rampart observing the scene beyond its confines. As my perspective changed, the ruins became more substantial and discrete. Individual structures revealed hidden connectivity and important aesthetic relationships to the whole. The missing art that I had sought was in the master plan; the grand design. Certainly, the network of criss-cross canals gave the place a Venice-like ambience and yet it all seemed terribly ad hoc; sort of thrown together: Ill fitting rocks that were hastily stacked in imitation of bastions in a homeland remembered from across the broad Pacific. The builders knew mathematics, had building skills, and had a form of writing and art. They just didn’t have the time or inclination for carving statues and adding embellishments. And, it appeared to be incredibly old.

I have spent much time investigating the ancient cliff dwellings in my home state of Utah. Some of those structures date from the time of Christ. I have cherished the essence of their antiquity, vividly etched in the weathered sandstone. Yet, Nan Madol seemed far older; from some prehistoric seafaring society that thrived in those distant days when man left the comfortable womb of Asia.

Occupied with these speculations, I joined my brother to take the typical tourist photos, posing here and there on the ruins like the classic Jungle Jim stereotypes, squandering the hours. As the shadows lengthened, we gave up our explorations and reluctantly returned to the boat. Our Polynesian boatman was relieved to see us coming, as the ruins are located on a tidal flat, and the tide was going out. Soon, our boat would be unable to reach the open waters of the bay.

The motor coughed into life, and we manoeuvred hurriedly around the growing sand bars and back into the bay. From the stern of the boat, I looked back at the shrinking silhouette of Nan Madol. As our boat skimmed away on the oily sea, the receding shoreline of Mangroves obscured and softened the outlines of the ruins. Gilgamesh or a Tibetan monk would have felt right at home there. For me, it had been a mystical experience. I turned my face into the spray from the bow and silently watched the distant horizon, like the builders of Nan Madol, awaiting destiny. The following morning, the airfield provided a further mystical experience, when, without warning or sound, the puddle-jumping jet from Guam materialized out of the clouds, precisely on time; tons of metal magically flying through the air to land exactly in the prescribed place.

The delightful Hotel Ponape

The outer wall of Nan Madol Fortress City made with 10-20 ton Basalt crystals

Getting into Nan Madol was a bit tricky at times

Getting into Nan Madol was a bit tricky at times

Past the outer wall and into the first interior plaza

Past the outer wall and into the first interior plaza

My scientist brother finds a 30 meter tunnel to explore

At the tunnel’s end are some strange symbols engraved in the hard basalt

At the tunnel’s end are some strange symbols engraved in the hard basalt

Our brave Polynesian boatman was fearless and helpful