It is hard to watch the images of the displaced people in the Middle East trying to find refuge from the madness of the religious wars going on there. It is especially sad to see the suffering of helpless innocent children who will be forever traumatized by the hapless flight of their families to regions of the world that are relatively peaceful and socially advanced. I’m afraid of the long-term consequences for the host countries, whose citizens have opened their hearts and wallets to the plight of these people. You see, the ‘religious’ conflict is a false –to- facts perception of what is really going on; I think a major contributor is that population density exceeds the carrying capacity of the planet in their region. The impact on the host countries will be profound and transformative, and not in a good way because of the clash of cultures and value systems.

Much can be learned as to the future of Europe and Asia from the seminal scientific experiments of John B. Calhoun in the 1960s. Here is a brief and very informative paper that summarizes the results of confining a population of lab rats as they grew from a pair of rats into something very frightening: Population Density

Unfortunately, I don’t have any answers or solutions. The deed has been done, and now our new ‘lab rats’ will show us the future of humanity without stringent population controls in place.

Now, on to another subject: A gift to my readers. What follows is a story that I published in my first book of short stories, “Smog and the Salv”

A Big Fish Story

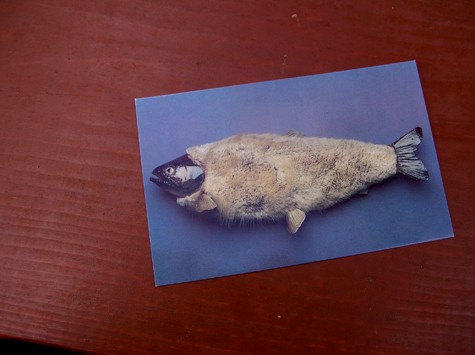

According to a Goshute Indian friend of mine, there is a tiny lake high in Utah’s Uinta Mountains that nestles in the caldera of a small extinct volcano. The Indians call it Iceberg Lake, and in it resides an extremely rare species of fur-bearing Trout. I know it sounds ludicrous, but I believed my friend.

You see, some years ago, after much coaxing, he introduced me to one of the rare delicacies of the Intermountain West: Sugar-cured Great Salt Lake Grasshoppers. These huge, yellowish insects are collected by the Goshutes when they appear every five years or so, and properly cured, they taste a lot like lobster or shrimp. That experience made me a believer, so I didn’t reject his fish story out of hand.

Determined to try my hand at fly-casting for these rare trout, I got my friend to draw a map to the lake’s location. The trailhead seemed to be at the top of Lung Blood pass at about 12,000 feet, and climbing up to that pass is no easy feat, especially when you are nearly 70 years old. From there, the trail snakes along the crest of the mountains, well above the tree line for about five miles, to finally drop down a little through thick patches of Lodge pole pine and Aspen to the lake.

So on a bright August morning, I started out with tackle, waders, and snacks stuffed in a small backpack, and fly rod case in hand. After the brutal climb to the pass, it was mid morning, and I sat down on a convenient boulder to eat a cheese sandwich and take in the view. It was nearly a cloudless day, with only a few puff-ball clouds hugging a mountain top here and there, and you could see clear into Wyoming.

After scouting around for a few hundred yards, I spotted the old Indian trail leading through a split granite cliff face toward the north. I slipped into the backpack and using my pole case as a walking stick, headed out along the high ridge. The trail was surprisingly level, and I made good time to the point where it dropped into the forest below. The lake was a bit of surprise; you couldn’t see it until you were nearly on it, but it was very deep, and about 400 yards wide.

I took off my gear, and after resting for a while, crept quietly down to the lake’s edge. I peered into the crystal-clear water and could see several fish swimming in the shallows. They looked blurry; sort of out of focus, and their heads were much larger than their bodies. This is a sure sign of a lack of nutrition, as I had seen it before in high altitude lakes that were stocked by the Fish and Game with Eastern Brook Trout. Very few survived the harsh winter at those heights.

I put together my fly rod, and tied on a tiny dry fly; a #22 Midge. On my first cast, a trout struck immediately. It jerked hard for an instant, and then the line went limp. I reeled in and saw that the fly was gone. The trout had swallowed it whole, and had bitten cleanly through the leader like some sort of Piranha. Those fish were damned hungry!

Shaking my head, I tied on a larger fly, and cast out again. I flipped the rod tip a few times to make the fly look life-like, and wham! Another trout chomped down, severed the leader and swam off, probably belching contentedly. I’m sure they were so hungry that they could digest the steel hook and feathers with no problem at all.

Disgusted, I reeled in once again, tied on another fly, and went through the same routine. Soon, I had gone through a half-dozen of my very best flies, and so I regrouped, tied on a much heavier leader, and attached big #12 Royal Coachmen and Silver Doctors. The outcome was the same; they bit through the leader and swallowed my flies. Soon, I was reduced to a few large terrestrials like grasshoppers and beetles in my tackle box. With their large heads, the trout swallowed them all, and none had even broken the surface to allow me to take a good look at them.

I couldn’t believe it; those trout had taken all of my lures and were swimming around with about an ounce of steel in their bellies. I searched through the bare hooks, spools of leader and line, and other paraphernalia in the box, looking for something at all to attach to the line. Nothing, nada. Wait a minute! I spotted a small horseshoe magnet that I had found last season and had casually tossed into the box. I know it was madness, but I was desperate. I tied it onto the line, and cast out, reeling in very slowly. Bingo! The magnet clamped onto the side of one of those trout, and I reeled in and flipped the small fish onto the shore.

It flopped around in the sunlight, the rays catching its glimmering golden coat of downy fur. As it flopped around, the magnet popped off, and I had a terrible time holding onto the little devil. It was a 12 inch acrobat, and the normal fish slime and the slick fur made it slip out of my hands every time I tried to grasp it. I did manage to flip it farther away from the shoreline, and exhausted, it finally gave up and lay quietly.

After it made its last gasp, I picked it up in both hands and examined it closely. Sure enough it was fur; close cropped and dense, covering its body from the tail fin up to the gills. By this time, I was tired and hungry, and consumed with culinary curiosity, I decided to cook and eat it on the spot. I made a ring of rocks and started a small fire within it. As it burned into coals, I sharpened the tip of a slender pine branch and speared it through the fish. I didn’t try to clean the fish first, because I was afraid of it slipping under the knife, giving me a nasty cut on the hand.

It didn’t smell too good as the heat from the coals scorched off the fur, but in minutes, the tender flesh was cooked. I got out the cheese, and one of the cold beers I had brought along. It wasn’t a bad meal. The stubble of fur gave it an interesting texture, and added a sort of almond flavor to the delicate trout taste.

I finished my impromptu meal, and seeing the sun was now across the zenith, I knew I had to start back to my car now, or take the risk of descending the pass in the dark. When I started up the car, I suddenly realized that I could never prove what I had experienced. I should have stayed to catch at least one more to bring home. On the drive back though, I realized that it was the Great Spirit at work. He wanted that lake and its unique inhabitants to remain a secret between me and the Indians. And, of course, I’ll never tell where it is.